How to Convert Portraits to B&W with Lightroom 4

In this tutorial I will show you how to convert a portrait (shot in RAW format) to a black & white image using Lightroom 4. By the end of the tutorial, and with some practice, I hope to teach you how to have full control over the look of your B&W images. While I chose this particular look for this particular portrait, Lightroom offers many kinds of different ways to convert your images to black & white, and so it’s impossible to put all the looks into one tutorial. Certain conversions fit certain images better than others, and it also depends on taste and goal of the author. In the future, I hope to make more tutorials for both black & white and color photography with different conversion methods and looks.

With that in mind, here is the image I will be working on:

1) Choosing the Starting Point

You may find that each of these ways may fit different images better, and so it is usually a good idea to see how they all look before proceeding with more thorough conversion techniques. Sometimes, depending on what kind of look you are after, you may even find this first step to be sufficient already. You may also find you like the final conversion of a particular look most even though you chose the starting point which, at first, may have looked the worst. The best thing I can do is find the starting point that’s easiest to work with. In the end, we will compare all three of them.

Here are the three basic ways you can use as a starting point to convert your image to black & white:

A side note – you can also use standard Lightroom presets as starting points, which you can find on the left-side panel. Still, the goal of this advanced tutorial is to teach you how to create a particular look from scratch, so that when there’s a need for a certain B&W conversion, you would know what to alter for desired effect.

2) The Fun Part

Lightroom was developed with an intended left to right, top to bottom workflow, but of course, frequently going back and forth is necessary in order to achieve what you pre-visualized. What we are aiming for is a sort of a medium-to-low contrast, bright image with smooth, bright skin-tone of our wonderful model. We don’t want our shadows to be very dark, but the blacks shouldn’t be light grey, either. With that in mind, lets move on to the actual adjustments, starting with the Basic Panel.

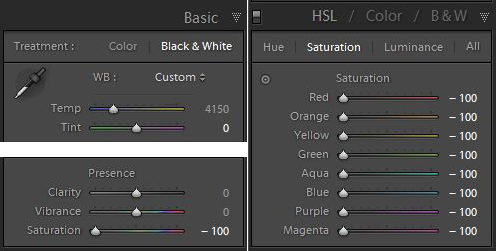

2.1) Basic Panel adjustments

You may find that the image already looks different, but we’re not stopping yet. Lets move on further down – I prefer to leave the Contrast, Black-White and Shadow-Highlight adjustment for much later as I like to alter certain color rather than just the tone at first. We can take a short stop at the Presence section of the Basic Panel and set Clarity to “-10″ – it’s smooth skin we’re after, and so we can be sure we don’t need this setting high.

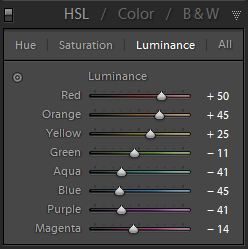

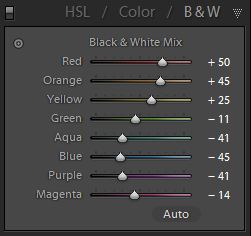

2.2) Hue/Saturation/Luminance Panel Adjustment

A side note – if you ever find yourself not knowing which particular color combination to adjust to make your main subject darker or brighter, you can always use the automated Lightroom tool, which appears as a dot in the HSL Panels. All you have to do is click on it to turn the tool on and then click-and-drag on the particular color range or area of the image to adjust its Luminance, Saturation or Hue. As you drag you will see the color sliders relative to your subject move left or right changing the values. Very easy to use and gives great results.

Now, the photographs have again changed significantly. In some cases they may even look over- or underexposed, but that’s not what matters – it’s how the tones look. Are they smooth? If you find the skin to be blotchy, you may want to readjust the Luminance settings or the White balance at the top of Basic Panel – both ways work, both lead to different results. Do you like the difference in the lightness of the tones when comparing them? In our case, the tones are quite nice in all three variants with the HSL Desaturated and B&W Treatment conversions looking best, if slightly overexposed and bright, but that we can fix by going back to the Basic Panel and adjusting the remaining settings. Before we do that, have a look at where we stand:

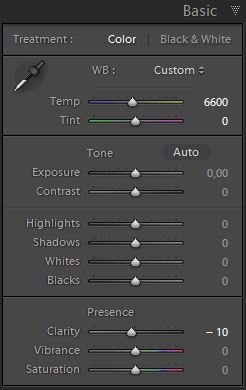

2.3) The Basic Panel Again

Previously, we left off with just the White balance and Clarity sliders moved. That hasn’t changed. Why I like Lightroom 4 most is because it has much improved black-white and shadow-highlight tone adjustment, and we are about to use this feature. Up until now everything also applied to Lightroom 3 users. Starting now, Lightroom 3 users will need to adjust accordingly with their Contrast, Fill-light, Blacks and Restore sliders instead of the ones I mention further on.

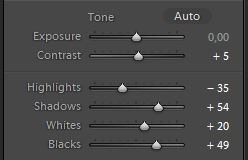

I’ve set the Highlights slider to -35 to bring back some of the details in parts of the image that may be too bright, so this saves me from having the brightest parts of the image being blown-out to a complete white. The skin is most important here. The change can be very subtle, but subtle and smooth is what we want. Moving on.

I’ve then set the Shadows slider to +54, which lightened the shadow parts of the image, the darker ones more so than the lighter ones. It gave the image even lower contrast, but what I want now is the quality of tones. I can tune them down later.

I’ve then set the Whites slider to +20 and the Blacks slider to +49.

What the screenshot doesn’t show is how I then altered the Exposure. Each conversion variant needed different adjustment in Exposure compensation, and so I set the HSL Desaturated image to -0.6, the Basic Panel Desaturated image to -0.3 and set the “Black & White” Treatment image to -0.8. You might be coming back to this adjustment depending on the photograph, but in our case it looks about right.

While all these steps may have looked like going back and forth between what we’ve already done, they actually allowed us to set the tonality of the image very precisely. I chose to lighten the image with the Shadow-Highlight, Black-White controls, but then tuned the image back down with Exposure compensation. Why did I do that? Why couldn’t have I just used the Exposure in the first place? Well, even though I brought the image back to the overall lightness I wanted (with future Tone Curve adjustments in mind), the Shadow-Highlight and Black-White adjustments still do their job of filling in the dark portions of the image and preserving those tones. Now we have plenty of detail in the shadows and the bright parts of the image, while being bright, are not blown-out, especially the skin tones, which are smooth and light. That is what we wanted in the first place, right? Having space to work with the Tone Curve later on was my intention here, and we now have that space. To give the images just the slightest initial punch, I set the Contrast slider to +5. I rarely use this slider as I prefer the greater control Tone Curve tool gives me, but your approach may vary – in some situations one doesn’t need greater control. So, lets move on to the last important adjustment.

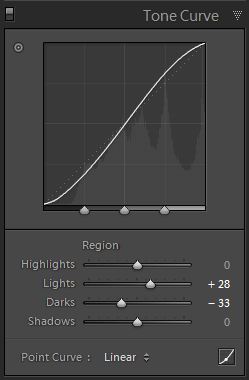

2.4) The Magic of the Tone Curve Panel

Detail Panel: I set the Sharpening setting to 70 and the radius to 1.8. Setting the radius to a higher value would increase micro-contrast, which in this case I don’t really need – I want the eyelashes and eyes a little sharper, that’s all. For this reason I also set Masking to 70 and left Detail at it’s default setting of 25.

Effects Panel: A little bit of subtle vignetting might suit this photograph. I set the Style to Highlight Priority, changed the Amount to a value of 20 and then, to make it more similar to the natural vignetting produced by the lens, I set the Midpoint to 9 and both Feather and Roudness sliders to +/100. Not wanting to make the vignetting too apparent, I usually try to make it look very mild to subtly aid the viewers eye towards my subject and away from the border of the image.

Last but not least – save the preset!

4) The Result

That’s it! Have a look at the results:

5) Was It Worth the Effort?

While in some cases working with Tone Curve or Contrast slider might be enough, it often doesn’t look nearly as good. Good, but not as much. Also, having the B&W preset with more settings makes it much more flexible in terms of light. Look at it this way – you have a modular camera system and a point-and-shoot. The modular camera takes more time to set up and is not as easy to use, but if something brakes, you only need to replace that part. The point-and-shoot is very easy to use and simple, it also can give great results. But if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. Flexible and easy to adjust is the key here, and once you’ve saved yourself that preset, it also makes things just as quick.

But that’s theory. Lets see if it really makes any difference. Below I have two images compared. The one on the left side (“before”) is one of the results I showed you a little earlier, and it involves the above-mentioned color and Shadow-Highlight, Dark-White adjustments. The one on the right was done by simply tweaking the Tone Curve (which now looks much more complicated, too: Highlights 0, Lights +31, Darks +63, Shadows -27). Both were converted to basic B&W by changing the Treatment at the top of the Basic Panel to “Black & White”. I tried to make the second sample as similar to the first one as I could without using any advanced techniques. Which one has the better skin look? While it also depends on taste, I would say the left sample looks much better and smoother. I didn’t use the Contrast slider for the second sample as it made matters worse. The Detail settings are identical. Take a look:

.gif)